For several years, U.S. authorities enforced a ‘wait in Mexico’ policy for people seeking asylum at the international border between these two countries, a policy which was officially rescinded only recently on June 1st, 2021. Ironically, it was a policy labeled ‘Migrant Protection Protocol’, or MPP, which did anything but protect migrating people, and actually kept them at greater risk.

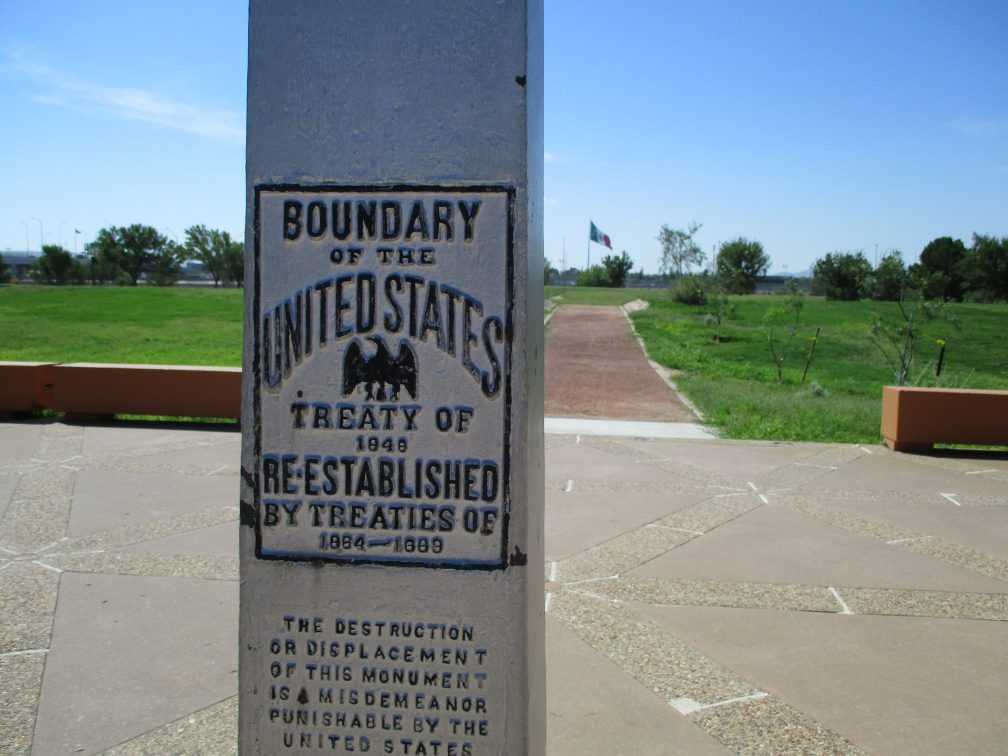

Instead, it forced them to fend for themselves in one of the most dangerous cities on Earth, Ciudad Juarez, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, while showing up at the international bridge to be taken to immigration courts in El Paso, Texas, USA (just over the Rio Grande river from Juarez) on appointed dates, to ask an immigration judge for asylum. The process for each case took over a year, involving at least four court dates spread out over that time. After each court session ended for the asylum-seekers, they were taken back to the bridge and forced to return to Ciudad Juarez.

I met Berta and her seven-year-old son, Francisco, when they finally won their asylum, and needed a place to stay in El Paso while waiting for a bus ticket to be reserved for them to travel to Virginia, by relatives already living there. Our Columban Mission Centre at the time was housing 30 to 40 migrating people per week, as part of an emergency coordinated response among over two dozen ‘hospitality shelters’ set up in our El Paso region. Berta cheerfully offered to help clean and order the two-story house, and cook meals, while her son played with the other children, and told the other volunteers and I about her journey from Honduras—nearly 3,000 kilometers away from us. It was a difficult story to relate to us, often leading her to sob and wipe her eyes.

“We managed to get a bus ride to the halfway point between Honduras and the U.S., in Monterrey, Mexico,” she said, “but when my husband, my physically-challenged daughter of 10 years old, my son and I got off the bus, Mexican soldiers began arresting people and chasing after them in order to force them to go back to Honduras.”

Berta held her son and ran one way, and in the confusion her husband carried their daughter and ran the other way. Berta and Francisco managed to escape the soldiers, but her husband and daughter were returned to Honduras. “I still don’t know whether they got back all right, I haven’t been able to call them,” she said, tearfully. “We continued on, finally arriving in Juarez a month later.”

In Juarez, church groups and humanitarian organizations provided shelter to many of the asylum-seeking families, and also managed to house people who were awaiting COVID testing results in hotel rooms designated for potentially infectious people by the city government. The Mexican government allowed those living in Juarez and other cities along the U.S.-Mexico border to legally reside in the country while waiting for U.S. immigration judges to hear and decide their cases, although it also continued to use their military to send people back to Honduras, Guatemala and other Central American nations, under pressure from the U.S. government.

Bertha was a good cook, and her son a bright little boy, inventing games and even challenging me to an hour of racing small model race cars, found among the donated toys, racking up points by aiming them at an obstacle course of domino tablets on the dining table, and trying for the highest-value ones. I have to admit that he helped me take a break from my schedule and rediscover the value of play for the overall well-being of otherwise busy people, as children are often adept at teaching adults.

They kept in touch, after getting their bus tickets for the three-day journey to Virginia, and settled into life among their relatives. Berta finally managed to contact her husband and daughter, still in Honduras, which was a huge relief for them. Now they contribute to the cultural richness of our society in the U.S. with their abilities and customs, and Francisco spoke to me of how grateful he was to me for taking the time to play. It seemed to create a lasting impression on him, an adult who valued his presence at an uncertain time in his life.

I continue to pray for them, and for their family to eventually be united again, as we in the U.S. try to establish a more humane system to welcome and protect those seeking refuge from poverty and other forms of violence, keeping families together, while recognizing that our own economic, foreign and military policies create the conditions that force people in Central American countries to abandon their homelands.

Fr. Bob and his family remain in our prayers.