A large Cross still stands near the main road to Lurigancho Prison in Lima, Peru. ‘No Mataras’, the inscription reads. ‘You shall not kill’. People come to stand or kneel there, to bring flowers, to pray. Sr Joan Sawyer, a Columban sister from Northern Ireland, who ministered to the prisoners in Lurigancho, is remembered more than three decades after her killing at the age of 51 on 14th December 1983.

The prison is just as drab, as unwelcoming, as overcrowded as when Joan walked the corridors as a much-loved pastoral visitor, serving hundreds of prisoners and their families.

Joan had access to two cell blocks, each with 350 men aged between 18 and 30 years old. She learned all their names and the addresses of their families. She learned the reasons for their imprisonment and whether they had legal aid. She was a familiar figure in the office of the Department of Justice in Lima where she went to verify the reasons for prisoners’ condemnation and the court’s decision regarding their sentences. She sought for the trial of those not convicted or applied for reduction of time in prison for those with a record of good behaviour. She visited their families, acting as messenger between them and the father, husband, son or brother who was imprisoned.

On that fateful day in 1983 Joan had two important messages with her, which the mothers of two of the prisoners had brought to her house early that morning. One was a small plastic jar of food, the other a small sum of money to help pay for legal aid.

Having signed herself ‘IN’ in the small office used by the chaplains and the pastoral workers, Joan went off to do her rounds and deliver her messages. But when she stopped by the chaplaincy office before leaving she found herself in a hostage situation with other pastoral workers and nine prisoners who had decided to break free of prison or die in the attempt that day.

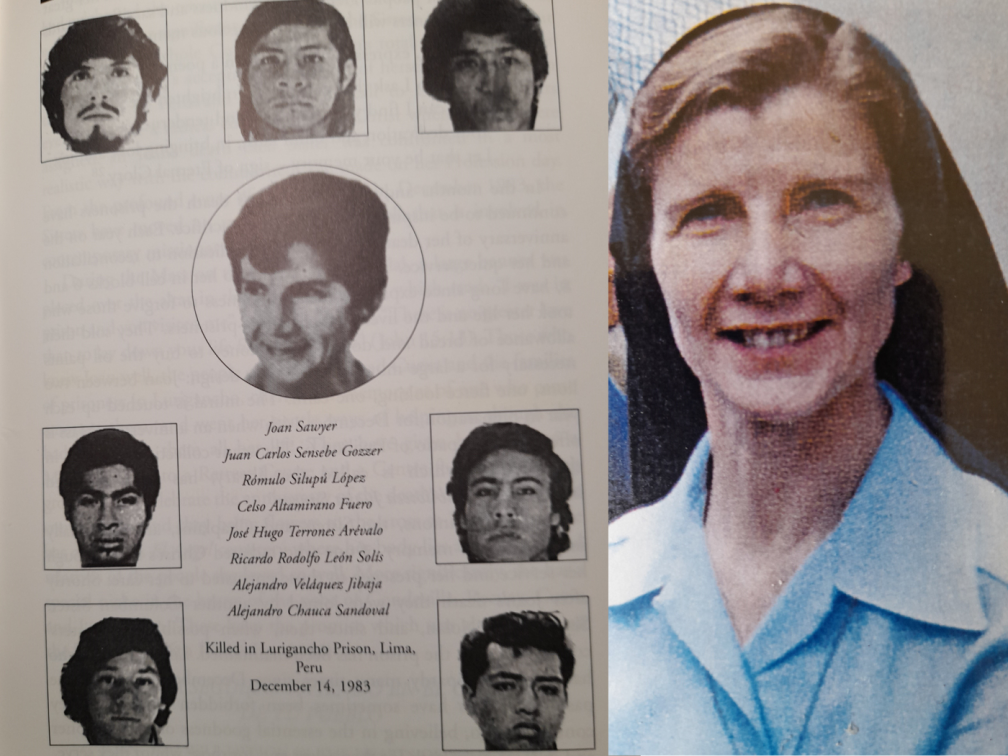

By late afternoon, the authorities had agreed to provide them with an ambulance and driver to take them from the prison. The hostages would be no longer in the custody of the prisoners whom they trusted. Joan was one of the last to enter the ambulance and sat on a small seat just inside the back door. As soon as the vehicle left the prison grounds shooting started. Police opened fire on the ambulance even with the hostages on board. Seven prisoners were killed, alongside Sr Joan. In death as in life she remained with the poor, with the prisoners, with her friends.

Cardinal Landazuri with some 80 concelebrants officiated at Joan’s funeral Mass. A large banner hung above the chapel altar: “I was in prison and you visited me,” (Matt. 25:36), “There’s no greater love than to lay down your life for your friends.” (John 15:13). People were in tears and they responded with a tumultuous ovation when the Cardinal denounced the cause and circumstances of Sr Joan’s and the prisoners’ deaths, and called for a thorough investigation of the incident.

Those who knew Joan well, the prisoners of Lurigancho and their families, cherish her memory every 14th December. They have given her name to a Mother’s Club, to a Retreat Centre and a Centre for school leaving companions, and they bring flowers to the huge wooden cross which was placed where the fatal shooting happened. The prisoners collected what little money they had to buy paint for a mural of Joan which is on a public wall in the city. The prison library was named after her, as was a road – and many little girls locally were called Juanita after her.

The Columban sisters remember the quiet, gentle woman and the prisoners who died with her. They say, “her simple poverty, her gentleness, compassionate and peace-making ways, were the source of her strength and influence.”

Sr Rose Gallagher, a Columban sister who knew her well, wrote this week: “The poet Patrick Kavanagh in ‘To the Man after the Harrow’ states: ‘For destiny will not fulfil, unless you let the harrow play’”

And maybe this is precisely what we can learn from Joan’s life and witness – it is in allowing the ‘harrow play’ in our own hearts and lives that makes it possible for us to hear the cry of the poor – capable of hearing the groans of the prisoners; of keeping them in mind as if we were in prison with them and thus being moved to compassionate commitment countering the evil still stalking the lives of too many in our world today.”