When an overwhelming wave of toxic red sludge crashed through her front door Kati Holtzer grabbed her three-year-old son. She threw him up onto their uprooted sofa and held him in place even while she herself was chest-deep in caustic waste. We know this because she called her husband to say goodbye, despite the chemicals eating into her skin.

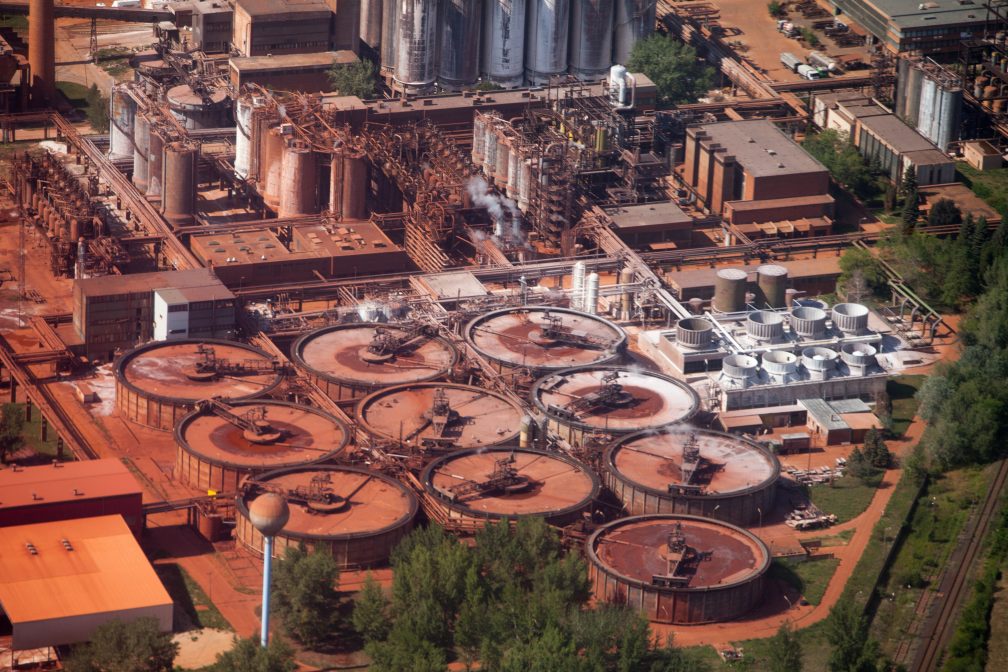

The catastrophe followed weeks of torrential rain in southwest Hungary during October 2010, when a crack in a reservoir at the Ajka alumina processing plant burst, inundating 2,500-plus acres of countryside with highly alkaline red mud. The sludge, a by-product from refining bauxite rock for industrial powder, was like a “mini-tsunami.” Ten people died and 700 fled their homes, marking the spill as the nation’s worst ecological disaster. The local River Marcal, a tributary of one of Europe’s main waterways, was inundated. Within days fish were dying in several rivers and by the end of the week a plume of the caustic waste had reached the River Danube which was winding through half a dozen more countries.

There is a long history of mine accidents in the Philippines. In 1996, millions of tons of mine waste from a dam of the Marcopper Mining Corporation spilled into a river on central Marinduque island, creating an environmental disaster. Several brave journalists who spoke out about the hazards of mining were murdered. Even priests were threatened. One found a gift box on the altar of his church containing two bullets and a bar of soap – two bullets for him and the soap to wash away the blood. This toxic waste killed significant freshwater and marine life. The 25-mile Boac river, which was the main source of livelihood for those who did not work for Marcopper, was declared unusable by government officials.

And in Latin America, earlier this month, BHP, the Anglo-American mining giant, resumed its operations at the Samarco mine in Brazil, five years after a dam disaster killed 20 people and polluted over 500 miles of rivers with toxic mine waste. BHP claims it is safe to restart operations. However, many in the affected communities whose homes were destroyed are still waiting for the promised 355 new dwellings.

The hazards involved in mineral extraction are regularly in the news, but do most people realise how regularly vulnerable communities and ecosystems are destroyed by the fallout from large-scale mining? Water resources are particularly at risk.

On World Water Day – 22 March – the Columbans point out that extractive industries by big mining corporations are often a threat to water quality and access, and there is little accountability when things go wrong. Water is essential for life, but extractive industries are increasingly destroying watersheds and demanding huge amounts of water for production. They are in competition with human, agricultural and environmental needs. We see that water pollution, as well as damage to and depletion of water basins, often creates extreme vulnerability for both the natural and human world.

The tension is that our society is very dependent on minerals. Nickel, for example, is important in the entertainment industry. Every CD and DVD is manufactured using a mould formed from pure nickel. However, when a Nickel mine was proposed for the island of Mindoro in the Philippines, local people and church campaigners campaigned against it. They warned that acid leaching, which is often used to extract the nickel, would contaminate the fresh water and rivers in the mine’s vicinity.

Columban missionaries were sympathetic since they have long supported mine-affected communities in the Philippines and elsewhere. Columbans are members of the London Mining Network which holds London-based mining companies to account by working closely with mining-affected communities.