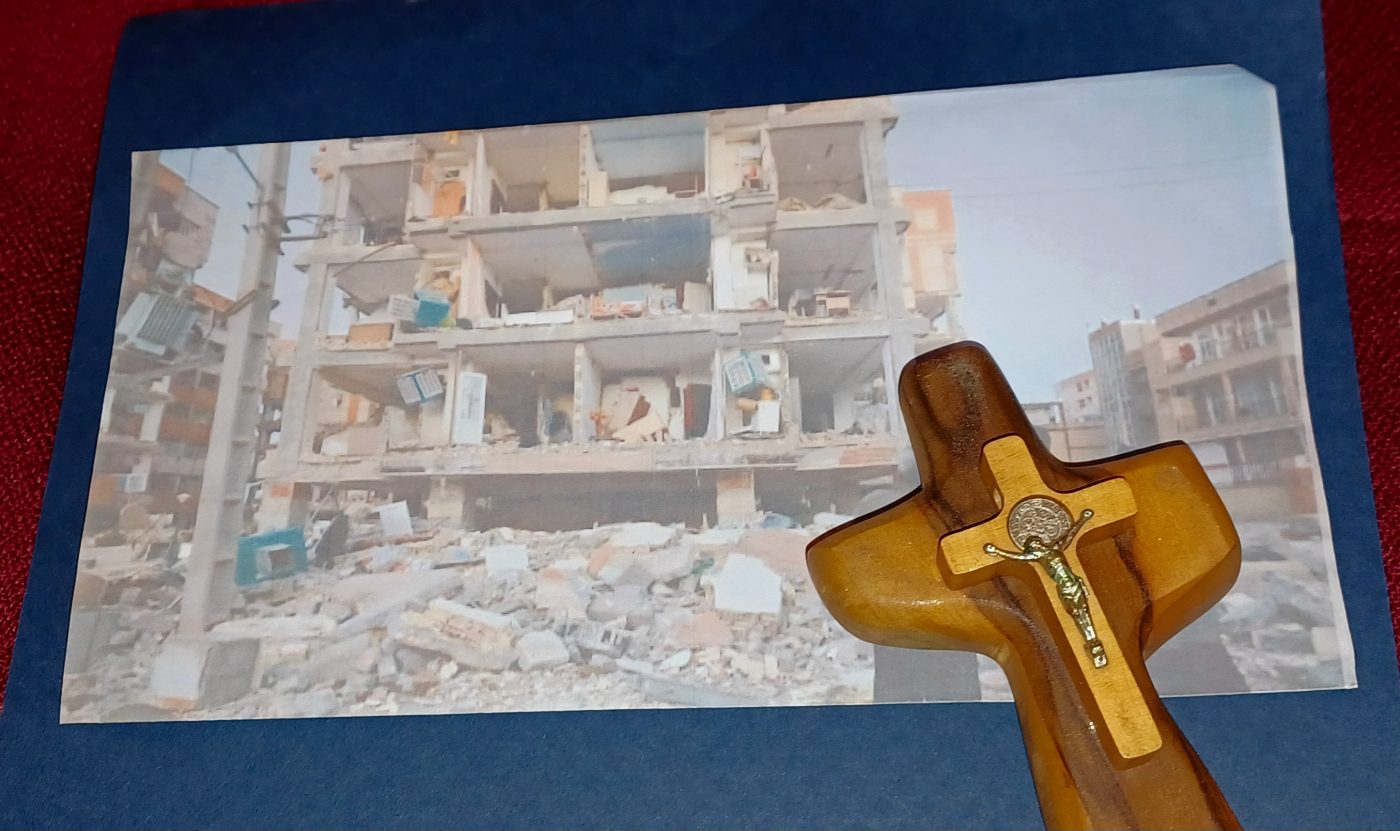

In 2010, the coast of central Chile suffered a massive earthquake with a magnitude 8.8 which was followed by devastating tsunami. As part of my dissertation for an MA on Applied Theological Studies at Birmingham University in that year, I decided to analyse the church’s statements and responses following the tragic events. The research led me identify emerging theological insights in the field of natural disasters (as well as potential strategies derived from them). In the aftermath of the most horrendous tragedy in Turkey and Syria last week, I believe the research recommendation still have some valid points, not only for Christian churches, but also for other faith communities that engage with the issue of faith in the face of ‘natural’ disasters. The following is a modified extract of the concluding section of that research.

The framework developed by Professor David Chester (University of Liverpool) and the theological insights of various liberation theologians, have guided us in this research to propose three general recommendations for faith communities.

1. The need for a theological reflection that goes beyond the meaning of natural disasters

Any relevant response of the church to these tragedies must convey an invitation to the faithful to engage in a theological reflection which avails of biblical, magisterial and liturgical resources. In the words of Gustavo Gutierrez, and following on the prototypical experience of Job in the Bible, a reflection which journeys through the ‘language of prophecy’ and the ‘language of contemplation’. First and foremost, there needs to be an invitation to mourn the losses and to journey throughout a wrestling with God’s will in a prophetic plea of protest – similar to the one found in the dialogue between Job and his friends. Then, there should follow an invitation to enter into the deeper mystery of suffering with a trusting heart, acknowledging the human limitation to make sense of any tragedy. Theological reflection on disasters still tend to rush into offering either retributive justifications or explanations which seek to find an educational value in the suffering of vulnerable people. Both of these are exercises are concerned with a search for meaning. We state with Marylyn McCord Adams that the significant question is not why God makes the innocent suffer, but how we can continue to trust in God amid a distressful situation. For Gutierrez both languages- prophecy and contemplation- eventually merge into a ‘silent praxis of compassion’ born of the contemplative, worshipful encounter with a God who is mystery. Consequently, in the face of natural calamities, and beyond efforts to search for meanings, faith communities must engage in a reflection leading towards that ‘silent praxis’ of compassion and solidarity through which the Christian faith offers healing to a broken world.

2. The notion of vulnerability and a praxis of compassion and real solidarity.

Chester’s stress on the necessity to articulate increasing dialogue between theology and disasters studies has made us aware of the need to find complementary areas in both disciplines in order to serve best the needs victims of disasters. Any relevant response to natural disasters must consider those e socio-political and historical conditions which increase the suffering and evil inflicted by environmental/political forces, particularly among the poor and marginalised in our societies. As hazard research shows, it is the underprivileged who suffer most losses in the face of these catastrophic events, therefore, it is vital that faith responses to tragedies are guided to uncover and tackle all the multidimensional variables which bring people to a situation of vulnerability. When the church incorporates in its discourse the notion of vulnerability, there it finds an opportunity to enhance its theological reflection on suffering and can contextualise more confidently its mission in post disaster conditions. Jon Sobrino finds in the victim’s situation the setting where salvation becomes possible. This is because the victims’ determination to survive in the midst of devastation manifests ‘something like the primordial saintliness’. Victims become God’s presence in the reality. This is why we say that that the victims of natural disasters bring salvation into the world since they unveiled the oppressive structures which inflict vulnerability.

All this has the power to awake in society a humanizing and profound sense of solidarity which sees victims and non-victims supporting one another. Furthermore, the recognition of vulnerability as a means of engaging communities in reflective action, provides the analysis of the victims situation with its rightful political- historical dimension. Local communities should be invited to engage with the sort of questions that Sugirtharajah asks: what patterns of neo-colonialism has this disaster produce in our society?

3. Enabling communities to a reflective practice on the occurrence of natural disasters

It is acknowledged that faith communities enjoy a high degree of cultural alignment with the population and particularly among vulnerable communities everywhere. This notion was also highlighted at the ‘Faith, Community, and Disaster Risk Reduction Forum’ in Melbourne 2009. The forum drew attention to a variety of factors which give faith communities a key role in disaster prevention and mitigation. Some of these include the following.

a) the facilities offered by churches/temples (which can be used for shelter of food distribution)

b) the church’s local immediacy (which allow its members to respond without delay to the needs of victims)

c) the church’s immovability ( they will stay in the place of disaster after the relief agencies leave)

d) the church’s institutional experience as provider of education, health as well as emergency relief.

Faith leaders must acknowledge the enormous potential of faith communities to respond effectively to the needs of the victims of natural disasters in coordination with other social agents. As stated above, the church must participate in promoting a culture of preparedness. The aspects of this culture of preparedness in which the church can participate may be the following.

i) Pursuing the building of effective relationships between the different faith community leaders and governmental agencies in charge of providing programmes of prevention and relief. Also pursue a stronger relationship with other faith communities, particularly of other Christian denominations. All this in order to promote operational coordination in the face of disasters.

ii) Promoting community resilience, particularly in the area of environmental sustainability, in order to motivate communities to seek resources to identify areas of communal/environmental weakness and the ways to tackle what may put at risk livelihoods.

iii) Helping the faith communities to articulate its own narratives on what constitutes disaster for them . This is an exercise which draws from to the past and present experiences of natural disasters but also from the liturgy, the biblical tradition, and other religious and nonreligious sources. Church leaders can use their authority to encourage communities to communicate those narratives to the civil authorities which deal with the effects of catastrophic events.